The Ironman World Championship, Kona, HI 2007

What follows below is my attempt to document my experiences surrounding the Hawaii Ironman. It probably makes the most sense if read straight through, but I’ve broken it up into several sections to make the reading easier (or easier to skim, whatever your preference). Yes, it’s long but so was my race! Enjoy.

Part One: The Race

Part Two: Getting In (Fifth Time’s the Charm)

Part Three: The Best Laid Plans

Part Four: The Taper

Part Five: Karma, Heat Waves and the Delaminated Wheel

Part Six: First Class in Coach

Part Seven: Check Out My Underpants, the Bachelor and My Speedsuit

Part Eight: Race Day, Endless Flow and the Snowplow

Part Nine: A Mystic Named Autumn

Part Ten: More Karma?

Part Eleven: Kupau

Part Twelve: Mahalo at a Player When You See One in the Street

The Race

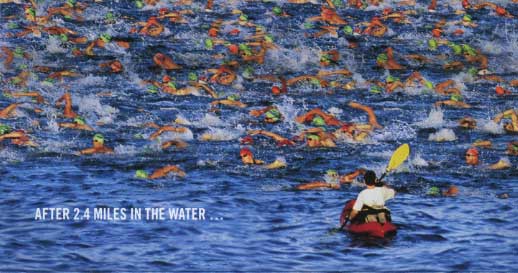

It begins with a 2.4 mile swim as athletes power through the waters of Kailua Bay, normally crystal clear, on race day made a tumultuous sea of churning arms and legs (and the occasional stray knee, foot and elbow). It is a one-loop, floating-start course, and chaos from the cannon all the way to the crowd filled boats marking the turn around 1 mile out into the bay. Below, in amongst the coral–only noticed in those rare moments of space, where a swimmer’s stroke grows long and smooth, fluid and relaxed–is a dazzling display of sea life, flitting about, oblivious to the frothy battle seldom more than 20 feet above. Between the coral beds lay sandy stretches often paired with cooler currents and swifter water pulling towards the shore. But almost constantly there are bubbles, and the feet ahead, and elbows to the left, and knees to the right. For those not strong enough to swim away from the crowd, there is little open water to be had, and every clean draft will eventually be fought for all the way back to the pier. For many this is a one hour rugby scrum, and most consider themselves fortunate to simply make it through this segment of the course without damage, major setbacks or injuries. To be sure, few, if any, have won the race in the swim, though many have lost it here.

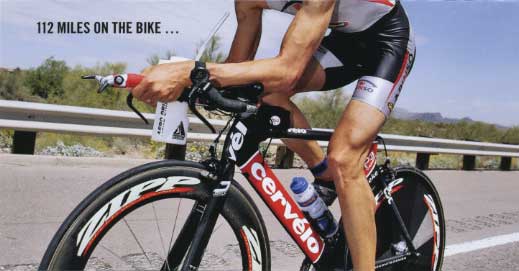

On exiting the swim, athletes must then navigate a 112 mile bike ride. It starts with a short loop through town–here athletes tear through the streets supercharged by the cheering spectators and the promise the day still holds–before heading north on the famous “Queen K” highway towards the turn-around at Hawi. From here on the course begins to grind, winding its way along the coast there is a steady barrage of quarter to mile long rollers before the final longer climb up to Hawi from Kawaihae. The wind is constant, head-on and interrupted only briefly by swerve-inducing side winds blasting in from the sea. There is about as much shade on this course as there are spectators now–none–and the sun begins to make its presence felt. The lava fields stretch out from the sea to the mountains in the horizon. They resonate with heat and cause the road ahead to shimmer. Aid stations appear to grow farther and farther apart, the winds provide no relief, they are a blast furnace of resistance. Then there is Hawi, the turn around and a moment’s respite. Only a moment.

Strong cyclists blast out of Hawi, using the long descents to power along at speeds of 40 plus miles per hour, hoping against hope to outrun the inevitable shift in winds that will turn a tail wind into a head wind later in the day. These descents are no tuck-and-coast affairs though, as the gusting winds are most intense along this stretch and less sure cyclists hunker themselves down on their bikes, bracing against the unpredictable and unseen side winds buffeting the athletes from the coast. Only intermittent rock outcroppings lining the road provide enough shelter for athletes to take their hands off their bars and quickly cram in as much hydration and calories into their mouths as possible, but these respites are brief and can be measured only in seconds. This is far from pleasurable dining and demands absolute concentration and resolve for athletes to stay on top of their nutrition. As the road returns to rollers, the day begins to grow long and reality starts to creep in. Race plans are confirmed, or altered, the first of many deals made and the foundation of a dream begins to grow or fall apart. The run looms ever closer yet not close enough, and the clouds, the clouds seen daily leading up to the race have not come yet, do not look like they will come at all, and the wind, the wind has not let up, good God the wind… until finally, there is Makala and the right turn off of the now despised Queen K, then Kuakini, and then Palani, and once again the excitement of the crowd.

And then there is the run. The run presents one final opportunity, one final chance to nail your goal or salvage a race going south, failure is not yet a possibility. What time is it? Do the math. You can still reach your goal. Go for it. You can walk if you need to, but only if you need to, and only much later, much, much later. But not now though, hopefully not at all. You get 17 hours to finish, how many do you have left? You’ll crawl the rest of the way if you have to. You’ll at least make it across the finish line. But walking is for later. Now it’s time to start running, time to give it your all, one last shot. Only 26.2 miles to go.

And at first there are the crowds, Ali’i Drive and finally some shade. This alone can power athletes up and down the rollers to the turn around at St. Peter’s Church some four miles up the road, and maybe even back again towards downtown. Because here there are the crowds, and hoses, the squirt guns, cowbells, excitement. Here there is energy to be found. But all too soon there is the turn up Hualalai to Kuakini before the final ascent of Palani. Too soon there is that left turn, the Queen K, and the sun, and the wind–that wind again–and the lava, and no one but the athletes shuffling between aid stations. The demons come hard and fast now, doubts begin to swirl. There is a lot of walking being done now and a lot of suffering. It is six miles to the Natural Energy Lab. Six miles until the pain really begins and age group athletes still on their way out can perhaps now just begin to see the overall contenders start to make their way back from what lies down the road.

And even the contenders look haggard, devastated, sweat caked on their bodies, saliva coating the edges of their sun-cracked lips as they tear themselves inside out racing towards the finish line. No normal person would willingly head towards what these poor souls appear to be running from, but the outbound athletes trek onwards in a steady parade of pain and suffering hoping to call themselves Hawaii Ironmen before the day’s end. Then it’s there, just in the distance, the turn into the Natural Energy Lab. Across the road, on the left, on the way back into town, the 20 mile marker lets the athletes just turning into the Energy Lab know: the pain you thought unbearable an hour ago will be a welcome respite from the pain you feel when you get here. If you get here. And if becomes more of question with each mile.

We signed up for, no, we PAID for this? Suffered and sacrificed to get here? What is this place, this scorched stretch of road leading towards the sea? Can it get any hotter? Who are all these people? These walking wounded? These stumbling zombies? Can a body simply combust in this heat or does it merely begin to melt on the side of the road, each step forward leaving behind a pool of flesh like candle wax dripping from a flame? Enough. It’s time to quit. To throw in the towel. Return to sanity. Make the pain stop. Time to turn in your number, jump in the back of one of those pickups heading back towards town, towards rest, a bed, air conditioning, friends and family, loved ones and beer, ice cold beer. No, ice cream. Ice cold anything but gels and Gatorade or cola and water. But just ahead is the final turnaround and the beginning of the end in sight. Every step forward is now a step towards the finish line. Back up on the Queen K the 20 mile marker calls: twenty miles of hope, six miles of reality. But what’s six miles after 134? Time to pick up the pace. Make a final push. For some the sun may begin to set here, or has already set–aid stations turning into glowing oases in the distance as the sound of shuffling footfalls and labored breath grows ever farther apart–for all, quitting now is no longer a thought. Not a possibility. Don’t stop. Keep moving. I’ll crawl from here if I have to. The miles may come slowly, but they come. And then suddenly there it is, Palani Drive, for the final time.

The crowd along the finish is audible now. Tired feet struggle to keep up with the pull of gravity down the last hill, the pull of the finish line. Left on Kuakini, it’s so close. Right on Hualalai and then right on to Ali’i Drive. Historic Ali’i Drive. The finish stretch triathletes the world over dream of running down. There is the banyan tree, stretching out across the road and towards the sea, in all its other-worldly grandeur, just partially blocking the view of the finishing chute. It’s so close now, maybe too close. The blue carpet begins, the crowd grows thick, and loud, the music pumps and the lights are bright. Savor the moment, tell tired legs speeding towards the finish line, driven by the cheering crowd, slow down, I want to remember this moment, make it last. Take it all in. I’m so glad to be done. How can I be done? How can I not want to be done? Is it over? It’s over! Congratulations, Mike Reilly shouts, you are an Ironman!

This is the Ironman World Championship in Hawaii, and every year, 1700 of the world’s fittest triathletes assemble on the big island of Hawaii to test their abilities, their strength and their conviction on a course like no other. It is a special place, a historic race, and for many the realization of a lifelong dream. Great stories are written here, inspirational stories, stories of epic battles and complete meltdowns, stories of courage, perseverance and overcoming adversity, stories of dreams realized and dreams dashed. Each year, 1700 athletes gather to compete and each year 1700 stories are written. This one is mine.